I believe in good buildings. I believe they can change lives, and that they will make a human future possible in light of the serious challenges we face, both in terms of income inequality and climate change. I also believe that right now there are too few of them to go around and those that do exist are too expensive.

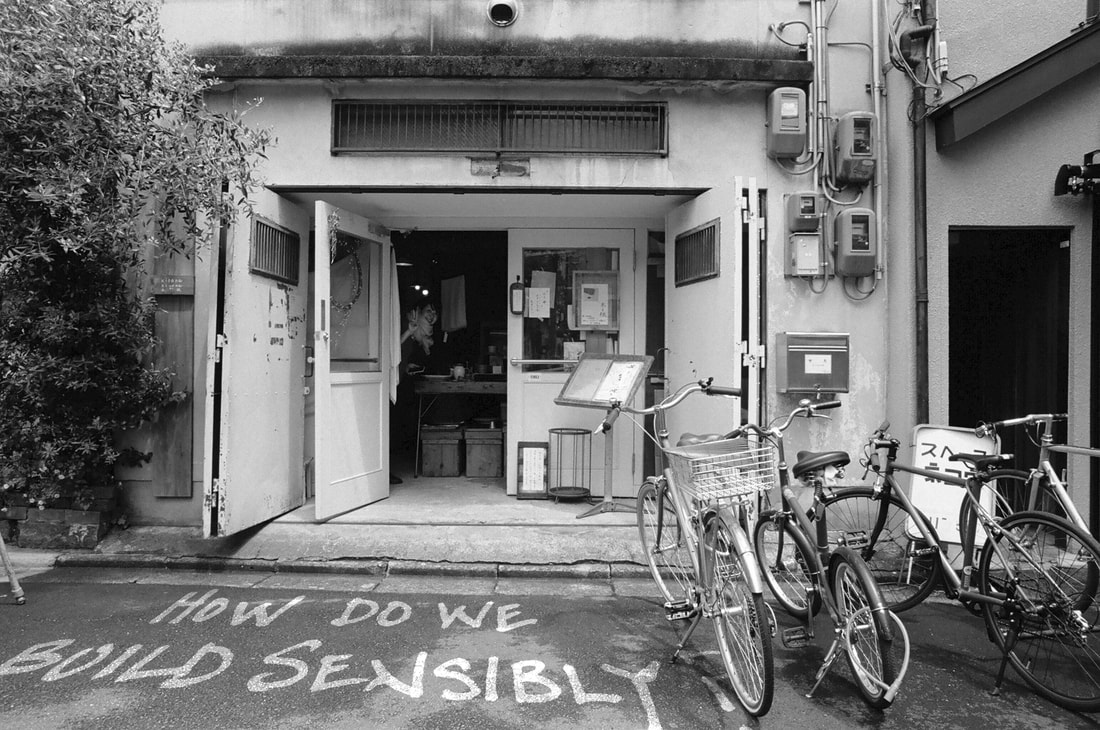

I think we can change this, and make better buildings available to more people. In architecture school I was preoccupied with the question written on the ground above: How do we build sensibly? Or in other words: How do we design sensible buildings? To me this means those that are 1) pleasing, 2) durable, and 3) easy to build. My understanding is that this requires less focus on artistic/expressive designs and more deliberate integration with construction and finance in order to bring real value to the end user at any kind of meaningful scale.

I have spent the better part of my life involved with building production in one way or another. The latest stage in this journey involves founding the company KIKUZU which designs buildings to be easily crafted off-site and delivered in a series of packages. I call them "kit-buildings" much in the same vein of the Sears & Roebuck houses from a century ago. KIKUZU.com is currently under development; more will be available shortly.

— AHR

Quincy, MA

Sept. 2021

I think we can change this, and make better buildings available to more people. In architecture school I was preoccupied with the question written on the ground above: How do we build sensibly? Or in other words: How do we design sensible buildings? To me this means those that are 1) pleasing, 2) durable, and 3) easy to build. My understanding is that this requires less focus on artistic/expressive designs and more deliberate integration with construction and finance in order to bring real value to the end user at any kind of meaningful scale.

I have spent the better part of my life involved with building production in one way or another. The latest stage in this journey involves founding the company KIKUZU which designs buildings to be easily crafted off-site and delivered in a series of packages. I call them "kit-buildings" much in the same vein of the Sears & Roebuck houses from a century ago. KIKUZU.com is currently under development; more will be available shortly.

— AHR

Quincy, MA

Sept. 2021